At 11:35 p.m., thirteen-year-old Oliver Peat turned the knob of his Lafayette HA-230 shortwave radio, swiveling his desk chair from side to side. He sat in total darkness, except for the soft, yellow glow of the radio’s dial. He had been listening to a variety show from Radio Netherland, and before that, a news broadcast from Moscow. Radio Netherland was one of Oliver’s favorite shortwave stations. Radio Moscow was just propaganda, but the broadcasters’ perfect English intrigued him.

His radio’s antenna was a fifty-foot-long copper wire that stretched from his window to a tree at the far side of his backyard. With his father’s help, Oliver had strung the antenna the previous winter when his dad gave him the radio for his birthday.

A National Geographic map of the world filled one of Oliver’s bedroom walls, with red, blue, orange, yellow, and purple push pins dotting the countries whose broadcasts Oliver heard. Close Encounters and Fantastic Planet movie posters covered the other wall.

Oliver twisted the knob to the right, tuning in higher and higher frequencies, passing through signals from Brazil, Norway, Alaska, and Israel, past a panoply of undecipherable languages and Morse code transmissions. Whenever he heard Morse code, Oliver transcribed it into his shortwave radio log, one of a half-dozen Composition notebooks stacked to the side of his radio.

Oliver narrowed his eyes and cocked his ear toward the shortwave. A new station! Goosebumps popped up along his arms, and a shiver cascaded from his nose to his toes. He uncapped his Bic pen with his mouth and scribbled fast to keep pace with the transmission, which repeated three times in the arcane vocabulary of dots and dashes.

Voyager location, right ascension seventeen hours, twelve minutes, forty-four seconds, declination, plus twelve degrees, zero seven minutes, fifty-one seconds, distance to Earth 154.611871 AU.

Then the signal went dead.

Of course, the signal is gone, Oliver thought after consulting his astronomy book and ephemeris. Whatever Voyager is, it’s now below the horizon, so it’s impossible to receive its transmission. Oliver spun his celestial globe with the constellations and poked a star with his finger. Voyager was in the constellation Ophiuchus, 14.4 billion miles from Earth.

He waited another thirty minutes just in case Voyager’s transmission returned, making sure the white vertical line of his radio’s tuner stayed precisely where he’d heard the signal, and then went to sleep.

“Dad,” Oliver bellowed as he jumped down the stairs two at a time.

“Olly, don’t run down the stairs, and hold the railing!” Steven said. “I’ve told you that a thousand times. You’ll break your leg or worse, your neck.”

“Kay,” Oliver replied as he landed on the carpet. He held a notebook with a black and white, mottled cover tucked under his arm and wore a canyon-wide smile on his face.

Oliver’s father glanced at his wristwatch. “What are you doing up so early on a Saturday?” He took a sip of his coffee and added another sugar cube. “It’s not even seven o’clock.”

Oliver bounded to the dining room chair next to his father, plopped his shortwave logbook in front of him, and flipped to the last entry. “Look, look.” The words rushed out of him like birds with a hurricane to their tails. “I picked up a signal from outer space.”

Steven tapped where Oliver had noted the time. “What were you doing up past your bedtime, young man?”

“Sorry, Dad.” He ran his finger under the log entry. “But read! I heard a signal from a spaceship called Voyager, which is farther from Earth than Pluto. It’s outside the solar system!”

“Voyager, you say?”

“Yes, the ship called itself Voyager.”

“I see.” Steven took another sip of coffee and then refolded his Boston Globe so Oliver could see the headline: Voyager Space Probe Launch Today, and the subhead: Probe to Explore Outer Planets and Beyond. Today was September 5, 1977.

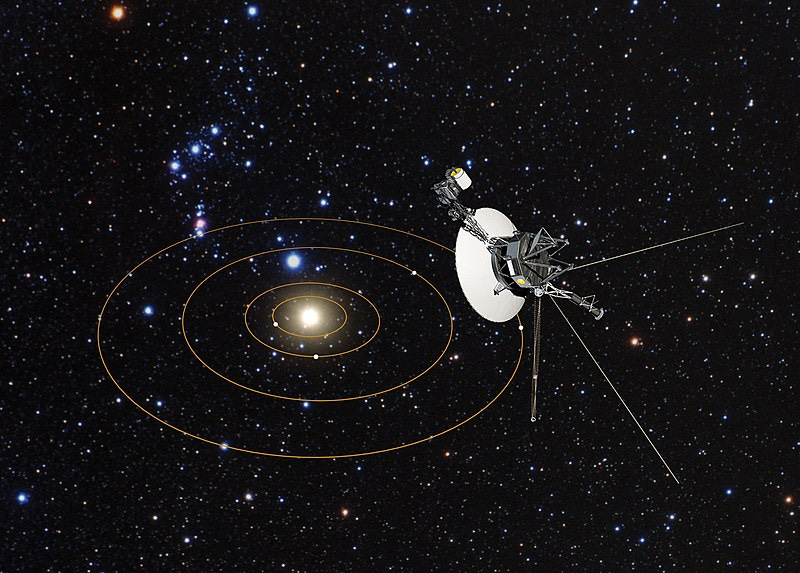

Oliver read how the plutonium-powered spacecraft would reach Jupiter in two years, Saturn in three, and, if the probe continued to function, leave the solar system around 2012. Voyager would continue to travel through interstellar space to the stars long after its communications systems ran out of power. Onboard was a map to Voyager’s home planet and a gold record with sounds and greetings from Earth, a message for beings on some distant world.

“You must have heard a radio program about today’s launch.”

Oliver shook his head like he was trying to clear a swimming pool’s worth of water from his ears. “Dad, read what I heard. I wrote exactly what the Morse code said. I heard the position and distance of Voyager. And when Voyager dropped below the horizon, the signal stopped exactly as it was supposed to.”

Steven ran his fingers through Oliver’s hair and kissed his forehead. “Let me see your logbook again.” He read Oliver’s log entry out loud and then declared, “I think you heard Voyager from deep space. I can’t explain it and I don’t understand it, but your logbook is fact.”

Oliver shot his fist in the air. “I knew it!”

“Now, what do you say that since you’re up this early, I make us blueberry pancakes—”

“—like Mommy used to make?”

“Like your mother used to make. And we’ll have breakfast in front of the TV while we watch Voyager’s launch. How does that sound, Olly?”

“That sounds great!” Oliver extended his palm for a high-five.

“Afterward, you can listen for more signals.”

“Radio signals are strongest at night.”

“Tonight, then. You can even have a chicken pot pie for dinner at your desk and scan the skywaves for Voyager.”

“I promise not to spill any food on my desk. Thank you, thank you. You’re the best dad in the world.”

A thunderous explosion woke Oliver at 4:42 a.m. His bed shook like it was in the grip of a furious giant’s hand. His night table teetered, and the wall fractured. Oliver pulled his wool blanket to his nose, froze in place, and watched his flip clock change to 4:43. Then the power went out.

“Dad!” Oliver screamed. He didn’t have to wait long because his father was already at the door when Oliver called for him. The thick, black smoke that shrouded Steven instantly filled Oliver’s room. Steven coughed as he made his way to Oliver’s bed. A second later, Oliver coughed , too, loud, hacking coughs that diminished in volume as the smoke replaced the oxygen.

Through the black, Oliver could see devil-red flames consuming his house. The fire seemed to burn even the smoke. Oliver’s skin stung everywhere.

He coughed one last time before losing consciousness. When he opened his eyes again, he was lying in the front yard with his shortwave radio in his arms. A fire tornado devoured what was left of his house.

His father lay next to him, dead. Later, Oliver would learn that his father died of a heart attack induced by smoke inhalation, and that a short in their fuse box caused the explosion. Oliver didn’t remember anything after his father burst into his room, and he didn’t remember rescuing his shortwave radio.

Oliver looked at his wristwatch: 10:48 a.m. There were no customers at Peat’s Toyota, not even any looky-loos, so he turned the volume of his childhood shortwave radio to the maximum. He carefully tweaked the frequency toward 9749 kilohertz, the same frequency on which he first heard Voyager. Over the decades, the radio’s tuner had lost its precision, but with a bit of fiddling, he was always able to find 9749 kHz.

His eyes misted and a lump grew in his throat.

He twisted the knob a little to the left, then to the right, and back to the left, his fingers moving with a jeweler’s deliberate precision. Oliver closed one eye and squinted to ensure that the marker and frequency aligned. The radio hummed, clicked, and whirred. There were a few seconds of static, followed by empty silence and then a familiar, soothing voice.

“I miss you, Olly.”

If you enjoyed The Day Oliver’s Father Died, I think you’ll also like my story, The Ferris Wheel.

Love is Stronger than Death

Touching end to an exciting story, Bill. Love your work.